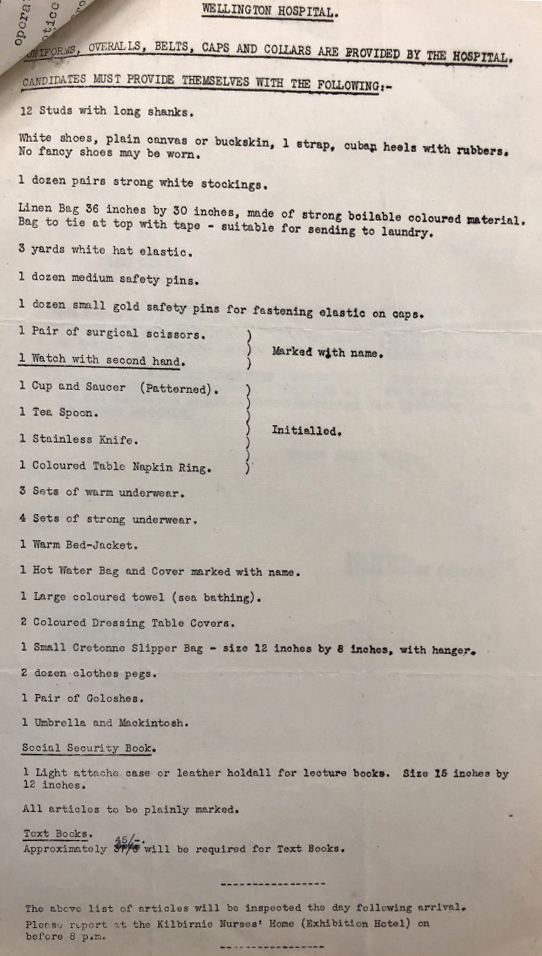

Candidates must provide the following...

A selection of historical nurse recollections from Wellington Hospital.

The following is part of a significant collection of historic digital content about Wellington Regional Hospital, providing insights into our history of health.

Edna Pengelly (b. 1874, d. 1959)

1 January 1904

"So began my first day in Wellington Public Hospital. In those days we provided our own blue uniform, later to be those of the hospital, with a change of colour to grey. For three months we struggled with our home-made “blueys”, providing our collars, cuffs and aprons. I may say in passing that the collars were murderous things, almost cutting our throats. The cuffs fortunately were removed while we washed, polished and scrubbed. During those first three months, the new probationer wondered anxiously whether or not she would be kept on. If so, she would change the colour of her uniform to pink, being called a “pink” nurse for some time, during which she would be taking greater responsibility and learning much.

We rose at 5 a.m., on duty at 6 a.m. This was in order to base the duties on an eight-hour period – three eight-hour periods in the 24 hours."

- Extract from “Nursing in Peace and War”, by Edna Pengelly

Caption for top image: Nurse Ellen Iris Schaw (1882-1970), who sailed on the 'Mahina' in 1916 to serve in the First World War. Wellington Hospital Archives, as gathered by Ron Easthope, honorary archivist. Further image details unknown; reproduced with permission from Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora.

Lizzie Ida Grace Willis (b. 1881, d. 1968)

January 1907

"I began my training in the Wellington Hospital under the Matron, Miss Frances Keith Payne and the Medical Superintendent, Dr John Ewart. Fifty-eight years ago there were no preliminary training schools for nurses. Raw recruits, as we were, it was straight into the wards for us – a real ordeal for shy, inexperienced girls.

The hospital main buildings consisted of six wards of 25 beds (supplemented with stretchers) and a side room of two beds, a kitchen with gas ring where sterilization was done between two basins. (The sterilizer came later). The bathrooms and toilets were at the end of each ward and were called “the backs”. Behind the main building were the Children’s Wards, isolation block, and a large two-storied building for the aged men and women. Shelters on the hillside were for tubercular cases. There were about six shelters, some with two beds and some with four.

The Nurses’ Home (just completed) was three storeys, with single rooms. We were very lucky, for prior to this the nurses slept in cubicles above Ward 5. There was a maid to each ward and she attended to the corridors and washed and polished the floors, and looked after the fireplaces. She also helped with the patients’ meals and washed up.

The nurses were called at 5 a.m. and reported in the ward kitchens for a compulsory cup of tea and to read the night report. On duty in the ward at 6 a.m. Each junior nurse took a side, to take temperatures, make beds, give out washes to patients who could wash themselves. Then swept and dusted.

Occupations for women were very limited. Many employers were still horrified at the idea of women in their offices. Even in hospitals the entrants had to be at least twenty-three years of age so that they began their work with a more realistic acceptance of the conditions. Dr. John Ewart, the Medical Superintendent and Miss Payne, the Matron, were people of the finest caliber. From them we received the best of training in every aspect of our profession. They never failed to stress that the care of the patient must come first. I can say here that this fundamental part of our training so deeply implanted by these two wise, devoted teachers and guides proved itself in later years. During the First World War, when New Zealand’s Sisters were seconded to the Imperial Army Nursing Service in England, Egypt, France or on Transport or Hospital ship duty it was a tribute to such training that the Chief Matron and other Matrons were reluctant to part with them.

Of course it was hard work. We had a seven-day week; an eight-hour day, which in special cases became twelve hours; three weeks' holiday and a late pass to 11 p.m. once in three months. Occasionally, on change of duty, there could be an all-night pass. One was on day duty for three months, and for the same period on night duty. As for payment, this seems to have had little relation to the hours worked or the physical labour entailed. For the first three months we received no payment, but after that 5/- a week and a slight rise in the second and third years.

Our uniforms or appearance could not compare with present-day wear, as the hospital had no money. But how proud we were to wear the patched, faded, lengthened uniforms showing where tucks, etc., had been let down, and only our aprons, cuffs and collars provided by ourselves were new...

At the end of three years, having passed the Hospital and State Examinations, I was appointed Sister of Ward 1 and later Night Charge Sister at £70 per annum. A strenuous but exceedingly interesting duty..."

- Extract from “A Nurse Remembers”, by Lizzie Ida Grace Willis

Kathleen Moynihan (b. 1911, d. 1992)

1932

"Our class of eleven only, plus one entering in May 1932, was the first intake for six months, possibly owing to the economic depression. We were the only students wearing pink uniforms. We had no preliminary course and there was no tutorial staff. Lectures were given by senior and junior medical staff, the Matron (Miss Cookson), and occasionally a nursing procedure was demonstrated by a ward sister - on "Dolly Chase" of course - no patients were used. All other learning was acquired in wards by practical experience.

Promotion exams were held every six months. There were no State exams until final registration. For the first year we were known as probationers ('pros' in colloquial language). At the end of the year, following success in passing an exam in anatomy and physiology, plus satisfactory ward reports, we were "signed on" for training.

Ours (1932-35) was the first class to have a Graduation ceremony, only because we suggested it. We paid for our own medals which were sent to us in 'Craven A' cigarette tins and which we handed in to the Matron's office so that they would be well and truly pinned on by the Chairman of the Board.

This first ceremony was held in the Senior Nurses' sitting room in the old Nurses' Home.

We had no study days or block system. Lectures were given at times to suit the lecturer. Those on duty had to return to their wards afterwards to make up the hour of absence from the ward. Those off duty were expected to attend all lectures."

- Extract from "Wellington Hospital Educating Nurses for more than a century", by A. L. McDonald and C. Tulloch

“In those days we provided our own blue uniform, later to be those of the hospital, with a change of colour to grey. For three months we struggled with our home-made “blueys”, providing our collars, cuffs and aprons. I may say in passing that the collars were murderous things, almost cutting our throats.” - Nurse Edna Pengelly