A Plastic Pioneer

In the chaos of war, amid death, several brave people worked to save as many people as possible, not only to heal injuries but also to allow them to reintegrate into society. One such New Zealander is Sir Archibald McIndoe, who pioneered several techniques to help reconstruct lives, including post-burn techniques and the walking skin flap.

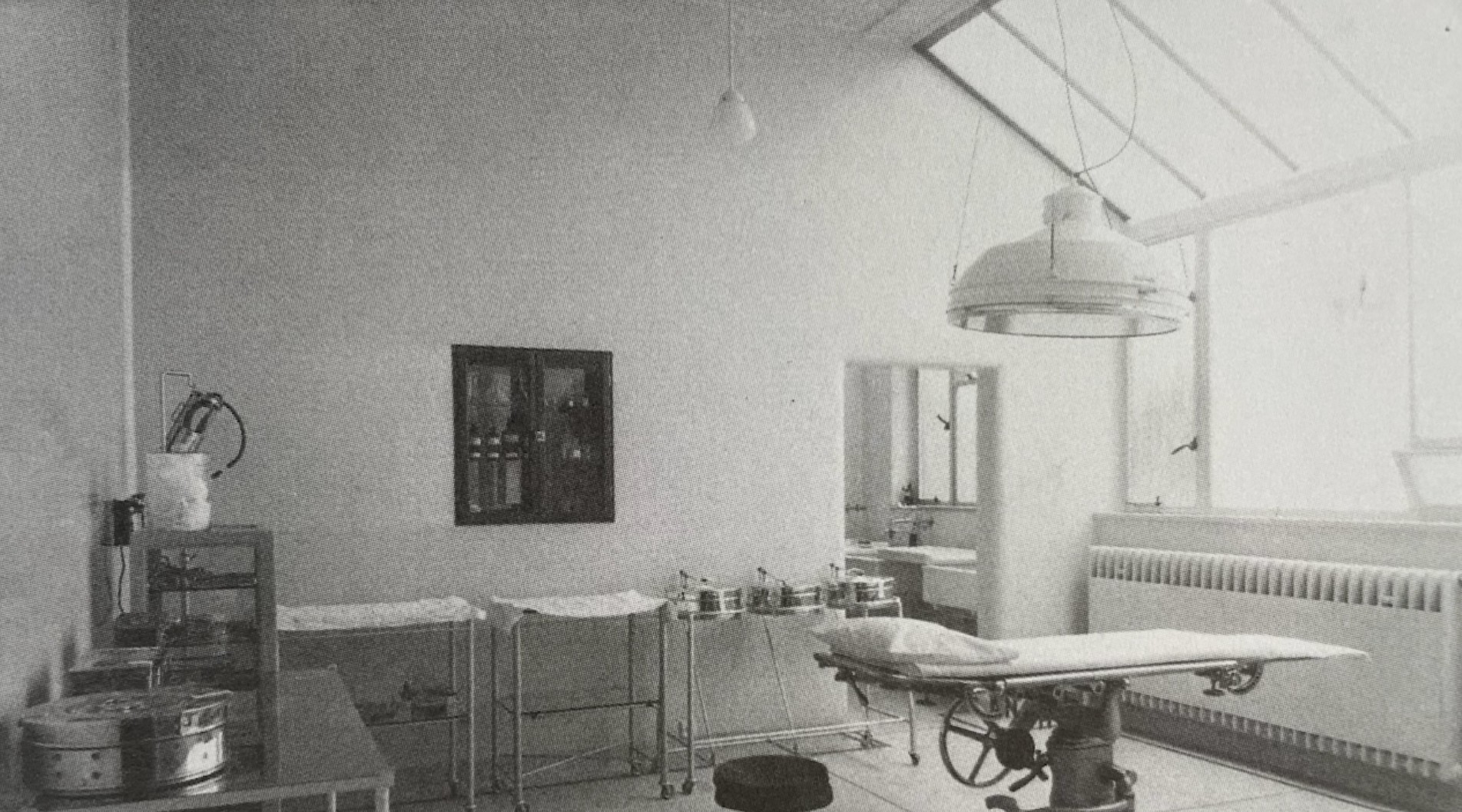

Sir Archibald McIndoe was born on May 4, 1900, in Dunedin, to his father, John McIndoe, a printer, and his artist mother, Mabel McIndoe. He graduated from the University of Otago in 1923. In 1924, he was awarded a fellowship to the prestigious Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, USA for a four-year term in pathology and surgery. During which he gained fame for his research on liver architecture, mapping out the blood vessels. McIndoe helped create the theory that, due to the liver's bilateral structure, there are two primary sources of blood flow. That one of these sources could be temporarily cut off during liver surgery without harming the tissue. After his residency at the Mayo Clinic, he became an assistant surgeon. The same year, he also married Adonia Aitkin. Two years later, in 1930, he moved to London and was invited to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital by Sir Harold Gillies, where he became recognised as a leader in plastic surgery a year later. In1932, he received his first permanent appointment as surgeon and lecturer in tropical surgery at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases. McIndoe was also appointed Plastic Surgeon at the Chelsea Hospital for Women, St Andrew’s Hospital and the Hampstead Children’s Hospital. In 1938, he became a consultant in plastic surgery to the Royal Air Force, and upon the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, he was assigned to the Queen Victoria Hospital at East Grinstead.

During the Second World War, McIndoe played a significant role in helping soldiers reintegrate into society. McIndoe and his team treated men, women and children who suffered burns and other injuries. This is where he developed and advanced several techniques that enable better recovery. McIndoe developed three highly notable techniques and innovations: his role in the banning of tannic acid jelly, bathing patients in saline, and playing a vital role in the development of the walking-stalk skin flap.

Sir Archibald McIndoe’s first significant innovation was the banning of tannic acid gel. Tannic acid is a plant-derived polyphenol commonly found in oak bark. However, during World War II, tannic acid jelly was commonly used to treat burns. The gel was distributed to British medical personnel for the treatment of burns. When applied to burned tissue, it dries up and tightens the skin, thereby reducing fluid loss from the wounds. However, Sir Archibald McIndoe found this method harmful. The tightening effect caused by tannic acid often leads to severe burn contractures. Therefore, when medics applied tannic acid jelly to burns, they often applied it to delicate areas of skin, such as the eyelids and fingers, which caused the skin to contract, making reconstruction significantly more difficult. Sir Archibald McIndoe campaigned within the RAF (Royal Air Force), eventually leading to its ban by the end of 1940.

His second major innovation was the introduction of saline baths. McIndoe observed the high survival rates of pilots who crash-landed in the salty sea and correlated the survival of those pilots to the healing properties brought by saline. It was a gentler approach compared to tannic acid. McIndoe regularly used and insisted on the utilisation of saline baths instead of tannic acid gel. He used saline baths to disinfect wounds and remove dead tissue, along with other debris. The use of saline water reduces the fluid loss because saline is isotonic. Additionally, saline baths help keep the wound moist, facilitating a faster recovery and easier reconstruction.

McIndoe's third major achievement is the significant development of the walking pedicle skin flap, which Sir Harold Gillies first introduced. The technique involves creating a tubular piece of soft tissue or skin, which is then slowly walked towards the target area by periodically severing and reattaching it until it reaches the desired location. This enables blood flow to reach the target area, facilitating better and faster recovery

Sir Archibald also believes that psychological recovery is as important as physical. He insisted that his patients should re-enter society, visiting shops, restaurants, and socialising in a town where they would not be stared at. He had appealed to the town of East Grinstead in Sussex to welcome his patients. He even changed the hospital blues given to a recovering soldier. McIndoe’s approaches allowed them to build confidence in their new appearance. At the end of the war, he helped a total of 649 soldiers. Thirty-nine of his first patients, who were allied airmen, formed the Guinea Pig Club, naming it after the experimental treatments they underwent.

At the end of the war in 1947, he was knighted. Later, he began farming in Kilimanjaro, Africa. He remarried to Constance Belchem in 1954. He is remembered as a figure of enduring admiration for his contributions to the medical sector. McIndoe’s pioneering work helped launch modern hand surgery, and he played a crucial role in forming surgical societies that promoted collaboration worldwide.

In 2025, Our Health Journeys continued our partnership with Saint Kentigern College in Auckland to challenge a number of students to conduct research into an aspect of the medical history of Aotearoa New Zealand. The students, ranging from Years 8-13, produced their research in written, oral, or video format and the top projects were chosen for publication to Our Health Journeys.