The beginning of the 20th century was perhaps some of the worst few decades of modern New Zealand health. Polio, typhoid and tuberculosis outbreaks were frequent and the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 devastated New Zealand populations. Further exacerbating the crisis was the Great Depression of the early 1930s which made it difficult for people to receive medical care. The result of almost two decades of these crises was the 1920 Public Health Act and a new emphasis on public health. The government recognised that many individuals were negatively affected by the decades and feared malnutrition in children, causing the New Zealand health department to become more receptive to new public health programmes.

Meanwhile a school in Caversham, Dunedin, was doing something unusual. They gave their students daily mugs of milk to help “delicate children to grow into healthy citizens.” Encouraged by the Caversham school and other local programmes around the country, Director of School Hygiene Ada Gertude Paterson campaigned for daily milk to be provided to all schools. It was suggested that milk could improve the health of children and provide sustenance when many were not properly fed at home after the Great Depression. Paterson’s enthusiasm for the idea and the recent success of a similar 1934 British Milk in Schools Scheme eventually resulted in Director-General of Health Dr. Michael Herbet Watt submitting a proposal for Paterson’s idea to his minister by 1936 which was soon accepted.

1937 Scheme

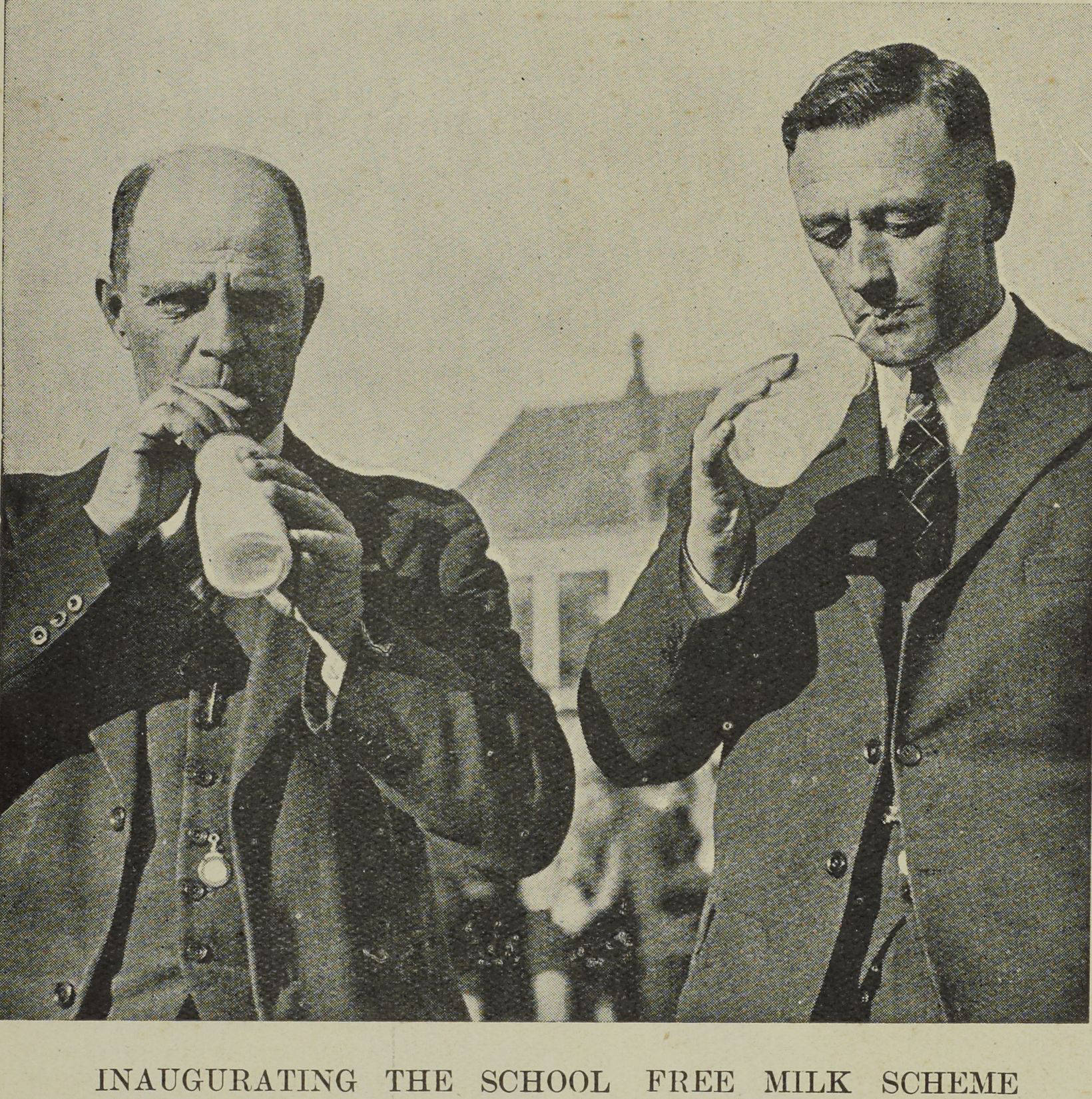

On the first of March 1937, the first batches of school milk were distributed throughout Auckland with around 27,000 children participating. The first deliveries were trials by the Auckland Council to see the scheme could be implemented at a larger scale. This was a success, quickly turning the project to a national project.

Due to the nature of the scheme, the Health Department worked closely with the New Zealand Milk Board, who handled most of the administrative duties - including organising milk supply, treatment, and distribution. Firstly, the Milk Board would source milk from local milk producer associations, which would then deliver to local treatment facilities where the milk would be pasteurised and packaged into small half-pint glass bottles with cardboard lids. Once packaged, the bottles would be crated and distributed to local schools alongside shipments of commercial milk, explaining why it was vital for the Milk Board to be involved with the scheme. To ensure all schools had access to milk, even when delivery of fresh milk was impractical, malt milk- or milk- powder was provided instead.

The crates would then be delivered to school “milk stand” - small structures outside schools that served to protect the milk from the elements. These stands were standardised by the government and could only be built out of certain materials - aluminium alloy, hardboards, asbestos sheeting, wood, or concrete blocks.

At lunch, the milk would be brought into the classroom – typically by students known as milk monitors – and would be drank under the supervision of their teacher. Schools were expected to wash and return the empty milk bottles back to the local treatment facility the same day the milk arrived; however, many did not do so.

Discontinuation

By 1967, scepticism about the nutritional benefits of school milk and the costs required to maintain the scheme led the Health Board to reconsider its continuation in the following years. It was decided that it would be discontinued as it was too expensive and not as effective as hoped, causing the scheme to end in 1967.

However, by 1983, interest in reintroducing milk in schools returned as groups of children in large cities started becoming malnourished. This revival was approved by the government but aimed to address the issues present in the first scheme. It was clear that many children were not interested in plain cow’s milk so strawberry-, chocolate-flavoured milk, and milk biscuits were considered. Vendors contacted schools directly and offered milk, giving schools an option to participate. This meant that milk was refrigerated for longer and avoided milk spoilage but also meant that milk was not subsidised by the government, meaning schools had to pay 30 cents a bottle - 5 cents of which was donated back to schools.

Problems

Despite the scheme’s simplicity, it was met with problems throughout its operation.

Firstly, many teachers and students did not enjoy the daily milk. An investigation by the New Zealand School Board also showed that the consumption of milk was directly correlated with how the teachers viewed the scheme. Some teachers were concerned with the safety of pasteurised milk compared to raw milk, while others doubted the health benefits of milk altogether. Numerous teachers also thought that drinking milk took time away from teaching, causing disdain for the project in certain areas.

Some children did not enjoy the daily milk rations. Some refused to drink milk as the bottles would be left until lunch in the milk stalls in the morning, causing it to sour under sunlight. Students also complain about “objectionable plugs of cream” on the top of the bottle, putting off many from consuming the milk. Certain children also attempted to avoid drinking their daily ration by getting notes from their parents. As one report in the investigation said, “The pupils not taking milk just will not take it.”

Secondly, there were doubts about the benefits of school milk. The Plunket society expressed concerns about the scheme. In a 1984 Auckland Star issue, the society’s Deputy Director of Medical Services, Dr. Ian Hassal, said, “Cows’ milk for growing children is not the most satisfactory of foods,” and “milk is poor in iron and children getting milk as the mainstay of their diet may be iron-deficient.”

These claims were supported by findings from researchers C.P. Anyon and K.G. Clarkson in the 74th Volume of the New Zealand Medical Journal published in 1971. Their study showed that excess cows’ milk could cause iron-deficiency anaemia in children - a condition where blood does not have enough healthy red blood cells. Excess calcium and casein in the milk binds with consumed iron and prevents its absorption. Since iron is vital for producing haemoglobin - the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells - the production of red blood cells is hindered, causing a decreased supply of oxygen to organs. However, development of iron-deficiency anaemia requires nearly a litre of milk daily when schoolchildren were only receiving slightly more than a quarter litre.

Another problem emerged in September 1963 when it was discovered that the standardised milk contained 4 times the amount of E. coli compared to other types of milk. Further investigation was undertaken in the following month where the New Plymouth Dairy Instructor, Mr. J. Bridger, identified a possible cause of the coliforms. He hypothesised that the issue was caused by the pasteurisation method required in the standardisation process.

To pasteurise milk, milk is heated up and then rapidly cooled so that most harmful pathogens are killed off. To reduce heating and cooling costs, pre-heated milk is used to warm the new cold milk, which is known as the regeneration process. New Plymouth factories had plate-type pasteurisers with similar regeneration systems, however re-used milk for heating often cooled down too quickly before it could be fully sterilised, allowing bacteria to survive the pasteurisation process.

Legacy

In 2013, dairy company Fonterra trailed giving small cartons of milk to primary schools in Northland to help children development in New Zealand. After the success of the experiment the programme was extended to all New Zealand schools. Now, the Fonterra Milk in School programme is present in more than 70% of primary schools, impacting over 140,000 children a day.

This story illustrates how bright ideas can be hindered by the limitations of technology at the time and misconceptions about health. It also invites us to consider what other historical schemes might be successfully revived with modern technology.

In 2025, Our Health Journeys continued our partnership with Saint Kentigern College in Auckland to challenge a number of students to conduct research into an aspect of the medical history of Aotearoa New Zealand. The students, ranging from Years 8-13, produced their research in written, oral, or video format and the top projects were chosen for publication to Our Health Journeys.